Malawi’s defining moment as past and present face-off

Elections

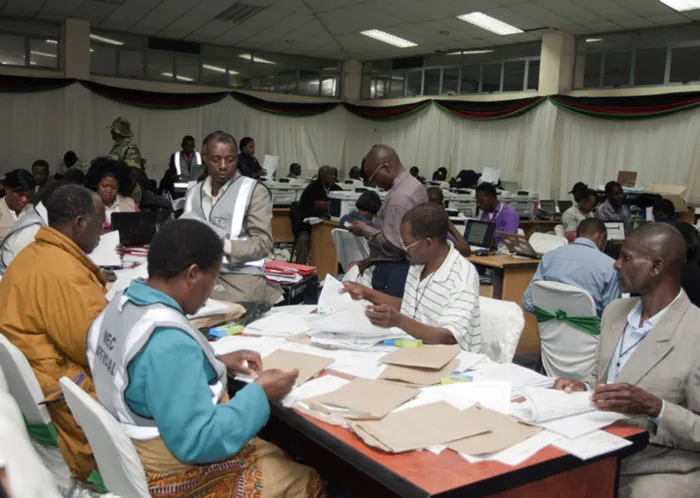

Electoral commission workers and other stakeholders recount votes during Malawi's national elections on May 24, 2014.

Image: Amos Gumulira / Supplied

ON September 16, Malawians will head to the polls in what is shaping up to be one of the most consequential elections since the country’s return to multiparty democracy three decades ago.

At stake is not just the presidency, but the question of whether Malawians will place their faith in continuity or turn back to a familiar face from the past. This election also holds broader significance as it reflects regional democratic trends seen in recent elections across Southern Africa, such as those in Zimbabwe and Zambia, where shifts in leadership have underscored the dynamic nature of democracy in the region.

The contest pits incumbent President Lazarus Chakwera, 70, of the Malawi Congress Party (MCP), against his predecessor, former President Peter Mutharika, 85, of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). It is, in many ways, a collision of Malawi’s present challenges with its political past.

More than 7.2 million Malawians have registered to vote. The MCP enters the race with a formidable structural advantage. Its Central Region base commands 3.2 million registered voters, a number akin to the entire population of a major city like Berlin, making it the most populated voter region. Lilongwe District alone has 1.2 million voters, with 826 000 in Lilongwe Rural, where Chakwera remains dominant.

In the Northern Region, once considered a swing territory since Malawi's first multiparty elections in 1994, momentum has recently tilted toward the MCP. This shift is noteworthy given the North’s historical unpredictability in voting patterns.

Chakwera’s choice of Vitumbiko Mumba, the Minister of Trade from Mzimba, as his running mate has shored up support in a region with more than 370 000 voters. For the first time in Malawi’s history, three straight opinion polls show the North leaning decisively toward MCP.

Mutharika’s DPP, by contrast, enters the election with a fractured base. His home district of Thyolo has just 253 000 voters. His running mate, Justice Jane Mayemu Ansah, hails from Ntcheu, which contributes only 172 000 voters.

Worse still, the once-solid Lomwe vote in the South is splintered among multiple contenders, including Vice President Michael Usi (OZAM), former central bank governor Dalitso Kabambe (UTM), PDP leader Kondwani Nankhumwa, and former President Joyce Banda (PP). Atupele Muluzi (UDF), son of ex-president Bakili Muluzi, is also in the mix.

The result is a crowded southern field with more than 317 independents contesting, diluting Mutharika’s traditional stronghold. A recent Institute of Public Opinion and Research (IPOR) poll shows MCP climbing from 26% to 31%, while DPP slipped from 43% to 41%. Sixteen percent of voters remain undecided, making them potential kingmakers, especially in urban centres.

Perhaps most telling is the “perceived winner” metric. Just months ago, Chakwera trailed Mutharika by 20 points. That gap has narrowed to six. In Malawian politics, perception often drives momentum, energising supporters while discouraging rivals.

MCP also has an edge in candidate deployment. It is fielding 220 parliamentary candidates compared to the DPP’s 196. Thirty-two constituencies have no DPP candidates, effectively abandoning an estimated one million votes; 30 of those seats are in MCP’s Central Region stronghold.

Chakwera’s first term has been dominated by crises. In 2022, Tropical Storm Ana destroyed infrastructure, flooding 19 districts and knocking out 30% of the country’s electricity. In 2023, Cyclone Freddy killed over 1 000 people, displaced 659 000, and devastated crops across the Southern Region. These disasters compounded a cholera outbreak and the lingering effects of Covid-19, which disrupted supply chains and drove up inflation.

Despite these setbacks, Chakwera’s administration managed to stabilise the country, mobilise relief, attract investment, and push forward development projects. Critics, however, argue that economic recovery has been slow. Malawi’s growth is forecast at just 2% this year, below population growth, and inflation has stayed above 20% for three years. Fuel shortages, medicine scarcities, and joblessness have triggered protests in major cities.

Corruption also looms large. While Chakwera promised to root it out, critics say his fight has been selective, with scandals continuing under his watch.

Mutharika, a former law professor who ruled from 2014 to 2020, urges Malawians to remember when, under his presidency, inflation fell and public infrastructure, particularly roads, improved. But his term was marred by allegations of corruption and nepotism. His narrow loss in 2020, after the courts annulled the disputed 2019 election, remains a painful memory for his supporters.

At 85, Mutharika faces questions about his age and capacity to govern, but his campaign insists he remains the DPP’s strongest option. “People remember that life was better under Mutharika,” said one senior party official. “That is why we are calling for a return.”

While it is seen as a two-horse race, Joyce Banda, Michael Usi, Atupele Muluzi, and Dalitso Kabambe complicate the landscape. Banda seeks a comeback despite the “Cashgate” scandal from her tenure. Usi, a former comedian turned vice president, appeals as a populist. Kabambe cites central bank experience, and Muluzi leverages nostalgia for his father’s presidency.

Underlying the political drama are stark realities. More than 70% of Malawians live below the poverty line, and millions require food aid after repeated failed harvests. Extreme weather, from droughts to cyclones, has left the majority, still dependent on subsistence farming, highly vulnerable.

On the campaign trail, Chakwera acknowledges the hardships but frames them as global and environmental crises beyond his control. Mutharika counters with a simple message: under his leadership, life was more affordable.

In the end, Malawi’s election may come down to turnout and undecided voters. The MCP’s stronghold advantage in the Central Region, its momentum in the North, and Mutharika’s weakened base in the South point to an edge for Chakwera. But the undecided 16%, many of them young, urban, and frustrated by economic stagnation, could yet tilt the balance.

“As a first-time voter, I feel crushed between high expectations and harsh realities,” shares Chifundo, a 20-year-old student from Blantyre. “We’ve been promised change for as long as I can remember, but nothing seems to improve.” Such sentiments highlight how crucial the youth vote could be in deciding the election’s outcome.

Malawians have a choice between continuity under Chakwera, who asks for time to finish rebuilding, and restoration under Mutharika, who asks them to return to the past. As Malawians head to the ballot box, one thing is clear: the decision they make on September 16 will define not just who governs, but the direction the country takes in the face of mounting crises and unfulfilled hopes.

Former Eswatini Deputy Prime Minister Themba Masuku has been appointed as the Southern African Development Community (Sadc) Electoral Observation Mission (Seom) lead to the election. He was appointed by King Mswati III in his capacity as the Incoming Chairperson of the Sadc Organ on Politics, Defence, and Security Cooperation.

On Tuesday morning, Masuku paid a courtesy call on Malawi’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nancy Tembo (MP). Minister Tembo expressed deep appreciation to King Mswati III for assigning Eswatini to spearhead the observation mission, particularly at such a crucial time for Malawi. She highlighted the importance of Eswatini’s leadership, noting that Malawi, as the current Chair of Sadc, is legally precluded from observing its own elections.

Later in the day, Masuku engaged with members of the diplomatic corps accredited to Malawi, including Commissioner Mlondi Dlamini, who represented Eswatini from Maputo, Mozambique. He also presided over the certification of Sadc election observers who successfully completed their training and are now set for deployment across Malawi. Among them is Dr Bonginkosi Dlamini from Mhlambanyatsi Inkhundla, who will be stationed in Rumphi District in northern Malawi.

The SEOM under Masuku’s leadership will oversee the deployment of 80 observers from ten Sadc member States. The observers will be assigned to all 28 districts of Malawi to monitor the elections and ensure the process is credible, transparent, and peaceful.

The Sadc Secretariat, under Executive Secretary Elias Magosi, has been tasked with coordinating and supporting the in-country deployment. The Sadc Electoral Observation Mission is part of the regional bloc’s broader commitment to democratic governance, peace, and stability in Southern Africa.

Get the real story on the go: Follow the Sunday Independent on WhatsApp.

Related Topics: