It may be true to the extent applicable to each circumstance that familiarity breeds contempt, but with this latest development, where Anglo-American is seeking to dispose of its controlling interest in De Beers, the familiarity of such repeating episodes is a tale of caution.

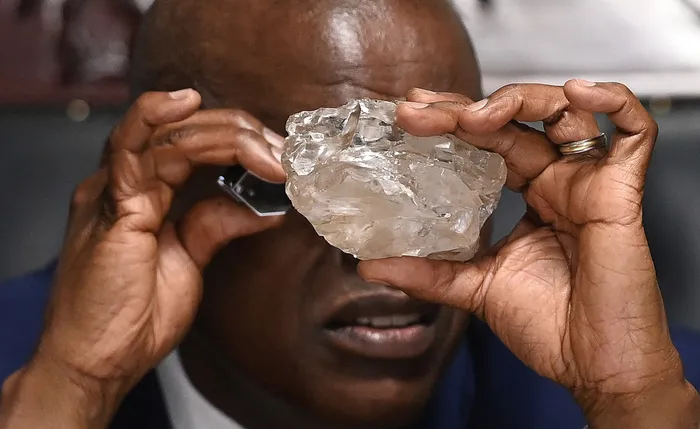

Image: Monirul Bhuiyan / AFP

THERE is something familiar about the story of a resource giant selling off its equity interest in some venture or holding corporation in Africa in general and southern Africa in particular, ostensibly on account of some sudden market conditions.

Its ring of familiarity, related to a significant extent to mineral resources, has a pungent odour of superciliousness and contempt.

It may be true to the extent applicable to each circumstance that familiarity breeds contempt, but with this latest development, where Anglo-American is seeking to dispose of its controlling interest in De Beers, the familiarity of such repeating episodes is a tale of caution.

Not so long ago, Shell Petroleum announced that it was ceasing downstream operations in the continental mainland of Africa. All that it sought to convey was that Shell’s political instincts were quintessentially doing two things, hopefully with deft.

First, they were definitely not leaving the African continent. And second, they were jettisoning onshore operations only to ascend up the value chain all the way to the offshore upstream exploration trough.

The exiting of Old Mutual from South Africa to be headquartered in London garnered a fair amount of vituperative discourse across the political spectrum of the rainbow nation. Old Mutual, for its part, insisted that it needed to move its capital assets to their primary listing jurisdiction, London.

Both Grok and the AI algorithms dispute such a sequence of events and insist that Old Mutual wasn’t going anywhere. Contrary to the country’s politicising of the Group’s intention, the AI geniuses suggest that Old Mutual was merely restructuring its different units. Imagine that!

The story of the diamonds of the Republic of Botswana and their veritable impact on the country’s political rhythms started with the discovery of diamonds in 1967, which, with concerted effort, resulted in the discovery of a diamondiferous kimberlite pipe two years later.

Debswana, the production joint venture between De Beers and the Government of Botswana, was formed in June of that same year. In 1975, the ownership of Debswana was equalised at 50-50 between the Government of Botswana and De Beers.

Beneath what seemed to be a calm and prosperous relationship, structured equitably between the partners, lay very deep chasms of discontent which were underpinned by the peremptory principle of resource sovereignty.

For one, notwithstanding their 50/50 share split of the production company, between 1969 and 2025, the diamonds that were allocated to the Government of Botswana remained capped at 25%. Only in February of 2025, when the partnership was renewed for another 10 years, did the percentages alter in 56 years.

Under the renewal terms, the share of Debswana’s production allocated to Okavango Diamond Company, the exclusive marketing company of the Government of Botswana, shall be revised upwards from 25% to 30% for the first 5 years and then to 40% for the following five years.

Even the South African gossip mill did not miss the opportunity to grind its own nuggets. The political elites in Gaborone have been setting up for a showdown around the Debswana contract, which has now been subsequently renewed, we are told. The stars and starlets of this glittering melodrama had many roles that elevated the Botswana presidential elections to a royal telenovela.

There is the president of the Republic of South Africa with his relatives, some mining magnates, the British royal family, Cherie Blair and the Zimbabwe customs officials. If the list had to be extended at the behest of the past president of Botswana, Mokgweetsi Masisi, it would include another former president of Botswana, Ian Khama, the Central Bank of Botswana, an owner of a private jet, some mercenaries, the South African Reserve Bank and oodles of missing Pulas.

Yet, all that haphazard concoction is merely a nuanced subtext for entertainment, out of which probably no deduction of consequence can be drawn. There is, of course, a more pronounced context playing out in the larger geopolitical canvas.

De Beers, the global diamond behemoth, is in a particular spot of bother. They reported a $1.9 billion (R31.7bn) loss for the first half of 2025, resulting in the slashing of dividends over the reporting period by more than 80%. For a company that earned $300m in 2024, it recorded a loss of $189m in just the first half of 2025.

The Anglo-American earnings from rough diamonds have been eviscerated by the increased availability of lab-grown diamonds. The numbers are frightening. While the lab-grown diamonds have seen a 15% annual growth rate over the past five years, with sales nearing $9bn in 2025, the woes of the rough diamond prices, on the other hand, have been alarming.

Following a declining trendline year-on-year, the sales of global rough diamonds have plummeted from $6bn in 2022 to just $2.7bn in 2024.

Save for price manipulation that has lasted for decades, what is driving the recent price decline is hard to determine with absolute certainty. It may perhaps be the fact that there are fewer matrimonial vows exchanged against the strength of diamonds that are forever. Perhaps!

However, the comparison done between lab-grown synthetics and naturally nurtured rough stones is too ephemeral to justify or support a rational analysis. Lab-grown diamonds and their dust have increasingly assumed a very important space in the rare and critical minerals debate.

Lab-grown diamonds, infused with nitrogen, a propensity which the rough diamonds do not have, are critical for space, telephony, vehicular and munitions industries. They are used in high precision manufacturing, ultra-fine polishing of semi-conductors, the machining of hard metals and ceramics in quantum devices, including the dissipating of heat in advanced electronic systems.

To be sure, China is responsible for the production of over 98% of machines that produce lab-grown diamonds. At that, they are responsible for over 95% of the global output of lab-grown diamonds.

On October 9, 2025, Beijing published a notification No. 55/2025 imposing export controls on superhard materials, including artificial diamond in powder and in single crystal forms, wire saws and grinding wheels made of artificial diamond and DCPCVD equipment and technology.

And while at it. We are reminded that the world’s largest producer of diamonds, Russia, is under an asphyxiating regime of sanctions.

So much of the diamonds produced in the African continent end up in Antwerp and then onwards to Israel via complex labyrinths of supply networks. Israel then becomes the second-largest supplier of polished diamonds to the United States after India.

For reasons that are difficult to explain, the United States maintains a high tariff regime on polished diamonds delivered from Israel. Israel then utilises the earned returns from the United States of America to fund the genocide in Gaza. This process makes a mockery of the Kimberley Process and makes everyone on that chain a participant in the laundering of blood diamonds.

In 2011, Anglo-American purchased the Oppenheimer family stake of 40% for $5.1bn, thereby raising their stake in that company to 85%. Without warning, however, in 2025, Anglo-American reduced De Beer’s book value by $2.9bn. In so doing, the value of the stock of the once dominant diamond monolith diminished to a measly $4.9bn, which is less than the $5.1bn it paid in 2011 for only a 40% stake.

Blaming Botswana for Anglo’s decisions or the giant’s woes that prompted the series of decisions that led to this critical moment is an exercise in futility. Besides, it is Anglo that has announced the fire sale of its entire stock of shares in De Beers. Botswana only responded with an expression of interest.

Going by the erudition of their President alone, the ambitions of Botswana are not only lucid but indubitably rational. Diamonds account for 33% of the country’s GDP and a whopping 80% of its export earnings. Such vantage or vulnerability, as the case may be, could not be left to the vicissitudes of chance.

The IMF, however, was quick to demur. They are not convinced that Botswana is adequately advised to embark on such an acquisition. They would prefer a corporation of their choice to acquire Anglo’s equitable interest. This way, the fate of Botswana’s GDP and its resource sovereignty ambitions could be easily thwarted.

Not accustomed to issuing threats directly, IMF honchos tend to resort to the mafia’s most cryptic line, lamenting that it would be a shame for a stable economy like Botswana to go up in smoke. The obfuscation of language in their long warning conceals threats whose extent can only be left to imagination.

The IMF has a big task indeed. Angola, through its diamond trading agency, Endiama, has also expressed interest in Anglo’s shares through a facility that would include Angola, Namibia, Botswana and South Africa.

Also, someone who has the facts is not talking to the IMF, or, as it is customary with these power contraptions like the IMF, they have no interest in the facts. It is not true that the demand for rough diamonds has softened. There is a plethora of supported research to justify the fact that the rough diamond sales have been increasing 12% year-on-year since 2022.

With the ensuing restrictions issued by Beijing in respect of machinery that produces lab-grown diamonds, the diamond powder and the lab-grown diamonds themselves, the future of rough diamonds is not yet entirely bleak.

All Botswana and its rough diamond-producing African brethren need to do is look beyond the hope that there will be enough new marrying couples in the future to sustain their productive economies. There is enough use for diamonds to supply the sophisticated industries that would take humanity into the mid-21st century.

And that the rough diamonds have now proudly entered the definitional horizons of critical minerals!

* Amb. Bheki Gila is a Barrister-at-Law.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media, or IOL.