If GBV was a disaster, Western Cape has made it a catastrophe

Opinion

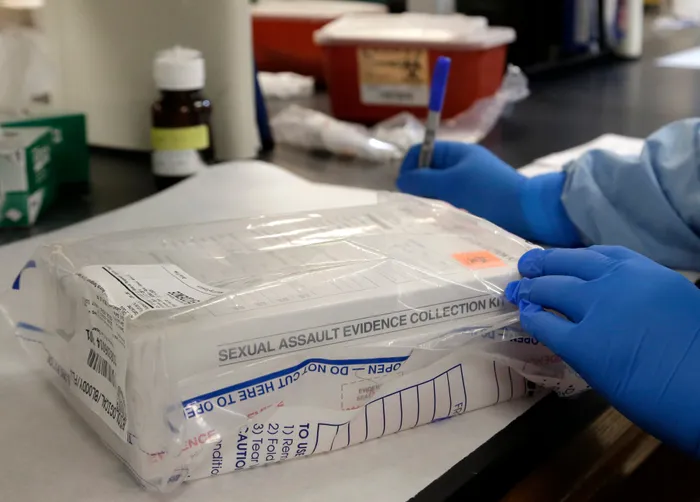

This past week, the nation woke up to an unforgivable reality: The Western Cape has no rape kits whatsoever.

Image: Pat Sullivan / AP / File

AT the beginning of this month, gender-based violence and femicide (GBVF) was officially declared a National Disaster in South Africa. However, this past week, the nation woke up to an unforgivable reality: The Western Cape has no rape kits whatsoever.

Although this was so vehemently denied by a scrambling SA Police Service (SAPS) spokesperson, Colonel Andrè Traut, mere days ago, an oversight inspection has revealed that the Western Cape’s central SAPS depot is completely bare — with zero D1 (adult) or D7 (child) rape kits available.

The so-called “city that’s working”, has been hiding a deplorable truth. The very depot meant to equip police stations with rape kits — the first step in protecting survivors — is standing empty. Not understocked. Not running low. Empty!

The most unnerving fact of the matter is that the Western Cape is consistently South Africa’s most violent province. It is not a coincidence or an oversight that rape kits are virtually non-existent, because this is a province that has consistently prioritised optics over action, favouring its delicate facade whilst violence ravages its communities.

The Western Cape is widely notorious for having the most severe problem with gangsterism. In fact, SAPS crime statistics reported that 91% of all gangsterism in the first half of 2025 came solely from the Western Cape. This is a province rich in wealth and resources, yet drowning in deep inequality and joblessness.

In fact, Cape Town has been internationally dubbed the murder capital of South Africa. Despite the picturesque landscapes, diverse flora and vibrantly colourful structures, this is a province whose natural beauty has long been used to gloss over the uncomfortable truth: that the vast majority of the population endures relentless crime, rampant insecurity, and economic neglect day in, and day out.

More critically, the Western Cape is the province that records some of the highest rates of sexual violence in the entire country. Statistics SA had already reported a staggering nationwide increase in sexual assault cases, including child sexual assault cases. However, the conviction rates remain dreadfully subpar.

Across the nation, corruption in law enforcement impedes tens of thousands of victims from attaining justice, and the absence of critical rape kits is a key reason for this. This means that beyond the unreported cases, those who do report assault are met with an indifferent “shrug”. This means that despite the systemic failures and the strategic “disappearance” of thousands of police dockets every year, violent crimes like sexual assault are being repeatedly perpetrated and subsequently ignored.

The very institutions that are meant to protect women are chronically underfunded, mismanaged, and complicit in turning a blind eye. The result is a system that punishes survivors twice: once through the violence itself, and again through the bureaucratic walls that block their right to justice.

The truth is that GBVF does not strike evenly. The women most at risk are often those living in poverty, in informal settlements, or on the outskirts of our metropolitan “modern” cities. GBVF harshly impacts those whose voices are easiest to ignore.

What’s even more disgraceful is the likes of SAPS Colonel Traut and the rest of our SAPS body, who so passionately dismiss the absence of vital police resources such as rape kits, knowing the devastating implications that this could have.

This is a complete dismissal of the rampant violence against women and children that is taking place daily in South Africa. This is feeding a blatant lie to the public that you are morally obligated to serve. This is corruption showing its face — not just in the background — but in the widely broadcast forefront of the SAPS institution.

The Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG) reported that between July and September 2024, over 10 120 rape cases were reported across the nation. This is despite the fact that only one in nine women who are raped report the crime to police, as reported by the Medical Research Council (MRC). This shines a stark light on the tens of thousands of women who are abused and violated in South Africa, without it ever being known, reported or addressed.

The absence of rape kits is not just a failure for survivors; it is a failure for our entire society. Without them, countless crimes go unproven, violent perpetrators walk free, and justice becomes nothing but a hollow word.

Furthermore, this lack of such a critical resource results in fear spreading, in communities crumbling, and survivors losing faith in a system that is supposed to protect them. Every absent kit is a message that violence is tolerated, that the system values bureaucracy over human life. It obliterates trust in police, in courts, and in our government itself.

When survivors see doors closed and evidence missing, they stop reporting. And when crime goes unpunished, it multiplies at a frightening rate. This is not a problem for a few; this is a national failure.

Our prolific Archbishop Desmond Tutu would distinctly reiterate that silence is not neutral, its complicity — particularly in cases of such significant proportions. These crimes demand screams for outrage and action, for the kind of accountability that radically and meaningfully changes things.

Every second we shrug, the nation gets weaker. Every moment we stay quiet, the people paying the price multiply. If we keep looking the other way, if we let indifference be our default, we’re watching our country rot before our eyes.

We know better than anyone that history won’t forgive our silence, and neither will the people living through it. The longer we wait, the higher the price we all pay.

* Tswelopele Makoe is a gender and social justice activist and editor at Global South Media Network. She is a researcher, columnist, and an Andrew W Mellon scholar at the Desmond Tutu Centre for Religion and Social Justice, UWC.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, IOL, or Independent Media.