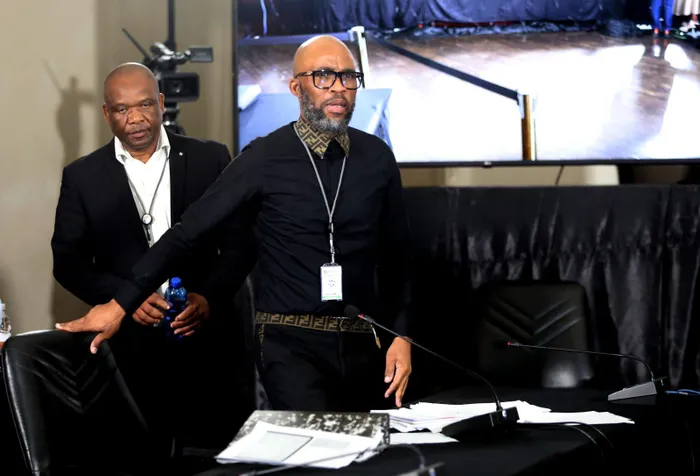

Vusimuzi "Cat" Matlala's appearance before the ad hoc parliamentary committee reopened yet another debate over the disturbing behaviour constituting the fabric of black townships.

Image: Thabo Makwakwa / IOL

THE appearance of Vusimuzi "Cat" Matlala before the ad hoc parliamentary committee reopened yet another debate over the disturbing behaviour constituting the fabric of black townships.

Tsotsis are revered in townships, and women also expressed their undying love for hardened criminals. Women expressed their undying love for a “lovable, clean and good-smelling” man, and others adored his outfits from international fashion houses.

This spectacle presents a side of the black community, from KwaMashu to Mitchells Plein (zones of entanglement), that we tend to overlook, maybe out of embarrassment. The mental wiring of many in the black community is among the most ludicrous in the sense that “soft” crimes are normalised and interwoven into our so-called cultures. People flock to churches and izangoma to seek “mahlatsi” (luck) and “umcebo” (fortunes), and go to great lengths to fulfil their dreams.

Many who have been to Durban beaches would confirm that stranded chickens roam a dirty coastline, full of colourful candles, sealed brandy bottles and other goods. In some cases, the high-level rituals associated with *ukuthwala* involve human sacrifice.

As the December holidays draw nearer, stock theft and animal sales will skyrocket as individuals deposit their “requests” for their good lucks to ancestors, gods and God.

For this reason, the surge in gambling and criminal activities in South Africa is not only a matter of addiction but also embedded in our social customs. The promise of algorithmic payouts on social media holds the same allure as young females twerking for their lives in front of their cameras for “lucks”, ooopsie, I meant likes and followers! Easy money and discounted goods are what make many individuals cut corners.

Even when a taxi operator forgets to collect a fare, many would keep quiet because they see this “soft” crime as their luck: “O Bhungane bangibhekile!” Others ascribe their luck to their God, “Modimo o phala baloi!” And anyone who makes it in this shady world of magic, be it a tsotsi or politician, is showered with praise and admired. “Mlungu”, “lenyora”, “guluva” and “nja ye game” are some of the superlatives reserved for those who have made it, either licitly or illegally.

It does not really matter whether one leads a clean or criminal life; what counts is money and possessions. Those who drive German machines, buy tons of booze or wear expensive brands become instant hits with women, and men alike.

The adoration of Matlala and general tolerance for corruption can be understood in this context, and maybe others as well. But definitely, not poverty, because many of us have a love-hate relationship with hardship. For example, the antithesis of success is rarely hard work but humble beginnings and divine interventions from God or amadlozi.

Nonetheless, the emerging pattern is clear: people are always hoping for a miracle or a freebie.

My friend Busani Ngcaweni, the Inanda Esquire, asked me to pen a piece historicising our faithful worship of township thugs. I guess I have to stick to the script before I get carried away, as the Msomi Gang and other naughty ones come to my mind.

The cultural adoration of the thug is not a new TikTok phenomenon, but a deeply historicised pattern. To historicise our faithful worship of township thugs is to recognise that the tsotsi figure has long been a complex anti-hero.

The early tsotsis of the 1940s and 1960s, with their slick American zoot suits and command of the street, were not just criminals but auteurs of an alternative masculinity. They owned the night, controlled the shebeens and possessed a swagger that stood in brave defiance to the state-mandated humiliation of the black man. They were agents of their destiny in a world designed to deny them any agency.

Since those early years, figures like the infamous Msomi Gang, operating primarily in Natal and later Soweto, were simultaneously feared and admired. The Msomi Gang gained notoriety not just for their violence but for their flamboyant style, their apparent ability to defy colonial authority, and their selective generosity toward their communities, a complex bandit-hero dynamic.

While their violence was rightly feared, the folklore that grew around their leader, Mzimkhulu “Msomi” Mpanza, painted him as a cunning, almost supernatural figure who outwitted the system. This narrative of the brilliant, ruthless individual triumphing over an overwhelming force is powerful and seductive, especially for a community that has felt perpetually overpowered.

That seed of admiration never died. It merely mutated.

This historical context was fused with the erosion of traditional social structures. The authority of the elders, once the bedrock of communal morality, was fractured by the migrant labour system and the economic pressures of township life. Into this vacuum of authority stepped a new priesthood: the ones with cash. The currency of respect shifted from wisdom and integrity to material wealth and the power it represented.

The gangster, the hustler, became the new chief, the new patriarch, because he could provide, protect and project an image of invincibility. He was the one who could bypass the dead-end of a factory job or a clerk’s wage and access the glittering world of consumerism that apartheid dangled just out of reach.

After 1994, when political liberation failed to translate into economic freedom, the gangster archetype found new life. The democracy-era tsotsi is no longer framed as a political rebel but as an economic rebel. Today, he is a hustler who has “figured out the game” when everyone else is trapped in a queue, waiting for emancipation that never arrives. In this logic, the tsotsi embodies a new fantasy: a shortcut through the ruins of inequality. He is the proof that “the system” can indeed be bypassed.

But what makes today’s admiration more disturbing is how normalised it has become. Unlike older generations who respected gangsters out of fear or necessity, the new generation celebrates them out of aspiration. The boundary between criminality and success has collapsed into pure spectacle. Today, we follow them, imitate them, admire their drip and post their quotes on WhatsApp statuses.

Their lives, no matter how violent, are turned into motivational content. Beauty and the Bester!

In fact, the moral confusion runs so deep that even legitimate success becomes suspect unless noise, expensive clothes, loud cars, flamboyant drinking, and exaggerated generosity accompany it. Quiet success is disrespected, and visible excess is revered. This tragedy runs deeper than many would care to admit. Township communities not only romanticise thugs, but they also reproduce the psychology of the “klevas”. The obsession with shortcuts, miracles and instant gratification is not limited to criminals.

This brings us to the critical intersection of spirituality and materialism, a uniquely potent cocktail in the post-apartheid era. Spiritual frameworks, such as belief in amadlozi (ancestors) and divine intervention, were co-opted into the frantic pursuit of this delayed modernity. Arguably, our tolerance for rampant corruption also falls in this continuum.

The ritual on the beach is not just about connecting with the ancestors. But it is a direct request for a BMW, a house in the suburbs or a lucrative government tender. The divine is no longer just a source of peace or protection, as it is now viewed as the ultimate venture capitalist. This is the fertile ground in which the modern figure of the “blesser” and the “guluva” thrives. They are the living, breathing proof that the ritual “worked”.

But what we forget is that when a politician, whose known salary could never account for his fleet of cars and multiple properties, is not shunned but celebrated as an “nja ya game”, it signals a moral collapse. Thus, this situation conveys that the end result (wealth) sanctifies the means, no matter how corrupt.

Therefore, to dismiss the adoration of Matlala as mere foolishness or moral decay is to miss the point entirely. It is a symptom of a much deeper societal pathology, a legacy of systemic violence, a crisis of legitimate authority and a spiritual crisis where faith has been harnessed to the chariot of hyper-capitalism. The “stunt” that Dareleen James pulled is thus out of frustration, as her black community is intoxicated by “mzulo” (quest to access quick riches).

The township’s love affair with the tsotsi is a tragic romance, born from the rubble of a fractured past and fuelled by anxieties about the present, the future and eternity. This is the story of a community searching for Saviours and Heroes in a landscape where traditional heroes have failed.

In their desperation, they find them instead in the dangerous, glamorous and destructive arms of the outlaw, who promises the world even if he has to steal it to give it to you. “Indoda must”, exclaim our black sisters as they urge brothers to go find.

The faithful worship of the township thug continues because the tsotsi is seen as having solved the core problem that democracy has failed to solve: the problem of poverty and power. The admiration is not for criminality itself, but for the ability to escape the clutches of economic fate by any means necessary. A “kleva” is seen as the one who has completed the final, tragic chapter of post-apartheid disillusionment.

Mzimkhulu “Msomi” Mpanza is no longer wearing Darks of London, Florsheims or driving Six Mabona. Guluva is no longer spinning “isandla semfene”. The new hero parades in a Christian Louboutin, has plenty of mashankura, drinks a cognac and dines in Dubai. A Fanonian reconstruction of wounded masculinity, maybe?

Siyayibanga le economy!

* Siyabonga Hadebe is an independent commentator based in Geneva on socio-economic, political and global matters.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media, or IOL.