Carol Paton’s ‘lies’ is no substitute for journalism

Editor's Note

Carol Paton has delivered a piece of speculative theatre masquerading as journalism.

Image: File

ONCE again, Carol Paton has delivered a piece of speculative theatre masquerading as journalism.

Her latest column, Revealed: Why the knives are out for PIC investment head is a textbook example of how narrative bias and lies can be weaponised to mislead readers and distort the truth.

Paton’s article is built almost entirely on conjecture. It constructs a fantasy storyline of corruption and chaos at the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) without producing a shred of new, verifiable evidence.

Instead, she drags the name of the PIC’s Chief Investment Officer, Kabelo Rikhotso, through the mud — linking his procedural suspension to the long-settled AYO Technologies transaction from 2017, a deal that predated his arrival at the PIC by nearly five years.

Let’s be clear: The PIC itself has confirmed that Rikhotso’s precautionary suspension “does not constitute a finding nor a pronouncement of wrongdoing”. Yet Paton treats this as an afterthought, preferring to weave a web of lies that implies guilt through repetition and insinuation. That is not journalism. That is a misinformation agenda.

What Paton fails to mention, or perhaps chooses to ignore, is the real and far more consequential story unfolding at the PIC.

As the Sunday Independent reported, there is a fierce internal battle for control of Africa’s largest asset manager, which oversees over R3 trillion in public funds. According to highly placed sources, the organisation is deeply divided, with one faction allegedly linked to former spokesperson Adrian Lackay attempting to destabilise the current board through covert manoeuvres, including the interception of internal communications and the circulation of damaging disinformation.

In that light, the timing of Paton’s piece raises serious ethical questions. Whether wittingly or not, her reporting aligns perfectly with this campaign to discredit the current leadership of the PIC. It substitutes fact with fiction, reducing governance processes into simplistic morality tales — always with the same villain: anyone ever remotely associated with AYO.

Let’s call it what it is: A lazy narrative built on selective outrage and lies. Paton’s consistent recourse to the AYO story, a transaction settled out of court two years ago, has become a convenient crutch, deployed to recycle suspicion rather than uncover new facts. Meanwhile, she overlooks the far more pressing issue: The systemic efforts by politically motivated networks to influence control over the PIC in the run-up to internal ANC contests.

The Sunday Independent’s reporting, by contrast, offers what good journalism should be — context, verification, and accountability. It tells the truth, even when the truth is complicated.

What Paton has done is not journalism; it is narrative engineering. It trades on reputation rather than evidence, and in doing so, it undermines both public trust and the integrity of the media.

In an era when institutions like the PIC are under constant siege from political and commercial interests, South Africa deserves better from its press. We need journalists who follow the facts, not the factions.

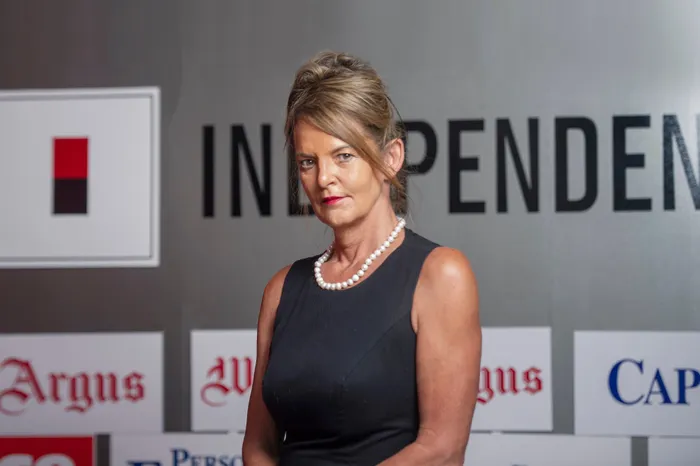

Independent Media’s editor-in-chief Adri Senekal de Wet.

Image: Armand Hough/Independent Newspapers

Until that happens, pieces like Paton’s will continue to erode the credibility.

* Adri Senekal de Wet is editor-in-chief of Independent Media.