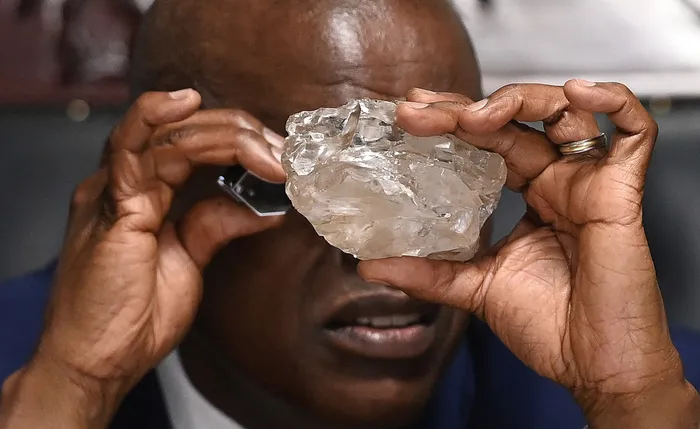

Former Botswana President Mokgweetsi Masisi looks at a large diamond discovered in Botswana. The collapse of the diamond dream is a sobering testament to a stark reality: in a world of rapid disruption, a failure of visionary leadership is the greatest economic crisis of all.

Image: Monirul Bhuiyan / AFP

FOR decades, Botswana was the African miracle, the shining example of how to transform from one of the continent’s poorest nations into a stable, middle-income economy. This remarkable ascent was built on a single, glittering foundation: diamonds.

Botswana is in the middle of a severe economic crisis, not because of “imperialism” or a global conspiracy, but because of a profound failure in visionary leadership.

The crisis is incomprehensible. Foreign reserves are dwindling, forcing the government to borrow. In September 2025, the health system neared collapse, prompting a state of emergency.

The statistics are just brutal. The World Diamond Council has tracked the average price of a one-carat natural diamond plummeting from a peak of over $6 800 (R119 010 at current exchange rates) in 2022 to under $5 000 by the end of 2024. For an economy where diamonds constitute about 30% of gross domestic product (GDP) and 80% of exports, this is not a downturn; it is a systemic collapse.

Botswana is having its Nokia moment.

In the early 2000s, Nokia was an undisputed, world-dominant king of the mobile phone industry. It was the Botswana of the tech world; efficient, profitable, and seemingly untouchable. Then, the smartphone revolution arrived. Nokia saw the touchscreens and app ecosystems pioneered by Apple and Google as a niche fad, believing their loyal customer base and superior hardware would see them through.

They were catastrophically wrong. They failed to adapt, clinging to a dying model until it was too late. Their collapse was not sudden; it was a slow-motion surrender to a future they saw coming but chose to ignore.

Substitute “Nokia” for “Botswana,” and “smartphone” for “lab-grown diamond,” and the parallel is chilling. For years, the signs have been there. The technological capability to create high-quality, chemically identical diamonds in a lab has been advancing rapidly.

By the early 2020s, it was no longer a sci-fi fantasy but a commercial reality, primarily driven by factories in India and China. These stones, ethically neutral and significantly cheaper, began capturing the market for smaller carats and fashion jewellery, steadily eating away at the base of the natural diamond pyramid.

Botswana’s story is a hard but necessary lesson for all of Africa. For nations sitting on cobalt, copper, lithium, or oil, the message is clear: your mineral wealth is temporary, not a permanent inheritance. The clock is ticking, not just on the resource’s depletion, but on its relevance. The world will always find a cheaper, more scalable, or more ethical alternative.

The lesson of Nokia was that no market leader is too big to fail. The lesson of Botswana is that no economic miracle is too bright to be extinguished by complacency. The collapse was not an accident; it was a choice. A choice to ignore the warnings, to trust in a fading brand, and to believe that “diamonds are forever”. For the sake of Botswana, one must hope that this painful lesson in reinvention, disruption, and adaptation is finally being learned.

Look at the contrast with the Gulf states, particularly the United Arab Emirates and Dubai. They understood a fundamental truth that Botswana’s leaders ignored: a resource-based economy is a ticking clock.

Oil, like diamonds, is a finite commodity whose value is subject to disruption. Decades ago, they launched a strategic, relentless, and visionary campaign to diversify. They poured oil revenues into building global hubs for tourism, aviation, finance, and technology. Today, while Botswana scrambles, Dubai’s non-oil sectors contribute over 70% to its GDP.

It is also convenient, and politically expedient, to point fingers at De Beers. The historic partnership has had its complexities. But to blame De Beers now is to miss the point entirely. The sovereign responsibility for a nation’s economic resilience lies with its government.

De Beers is a corporation; its mandate is to adapt and survive, which is why it is not a coincidence to see the company now also exploring synthetic diamonds. Botswana’s mandate was to secure the future of its 2.4 million citizens. The state had the capital, the sovereignty, and the warning signs to build alternative engines for the economy. It failed.

Botswana’s crisis was not an accident. It was a choice, a choice to ignore shifting consumer demands, to dismiss technological innovation, and to believe in a mirage of perpetual resource wealth.

The lesson here is not for Botswana alone, but for every resource-rich nation on the continent. The 21st century will not be kind to those who place their faith solely in minerals that can be dug from the ground, for the market will always find a cheaper, more ethical, or more innovative alternative.

The true, enduring resource for Botswana was never the diamond itself, but the revenue it generated, capital that should have been invested with urgency into building a diversified, knowledge-based economy.

The collapse of the diamond dream is a sobering testament to a stark reality: in a world of rapid disruption, a failure of visionary leadership is the greatest economic crisis of all.

* Phapano Phasha is the chairperson of The Centre for Alternative Political and Economic Thought.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, IOL, or Independent Media.